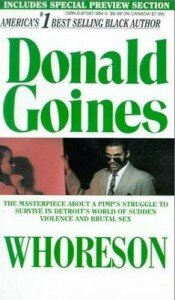

Often, early works by an author—the fancy word is “Juvenilia”–wear their influences on their sleeve. They sometimes feel like they were written by another person altogether. Interest usually stems from a scholarly game of “spot the older more interesting author” and not the typical enjoyment/analysis of a novel. The reading’s framed around questions like: How does this resemble the later, more mature works? How does it differ? What’s been added? What’s been whittled away? Whoreson, Donald Goines’ first book, but published after Dopefiend is best viewed as a piece of Juvenilia.

There’s a few issues with giving Whoreson this label though. The book belongs to a genre where unfortunately, quality wasn’t—and still isn’t—of much interest and so, the weirdo stylistic changes, the narrative threads that are just abandoned, etc. don’t really matter. If the book’s “street” enough, if it’s lurid, and about “the life” it’s gonna be published and embraced by readers.

Also: At least in age, Goines was not a young author. He wrote Whoreson during a prison sentence for grand larceny—the sentence began in 1969 and ended on December 1, 1970—so he was thirty-two or thirty-three when he wrote it (Allen 96-101). It was published in 1972, a year after his second manuscript, Dopefiend which is significantly better, more structured, and all-around more Goines-ian than Whoreson. Goines was probably thirty-three when he started outlining Dopefiend and thirty-four when it was written and published. As I said last month, it was Holloway House that edited the prison manuscript Whoreson and Goines’ sister, presumably along with Holloway House, that edited Dopefiend. Perhaps this explains the notable differences in quality.

Whoreson was also written in prison and as a result, much more closed-off from outside influences. Prison’s the most ideal and least ideal place to write a book. An incarcerated author certainly has a whole lot of free time, but the conditions could not be worse for writing. Good writing comes from outside experiences and stimulation, not being stuck in one place. It’s no wonder so many prison novels and memoirs burst with emotion but feel claustrophobic and disturbingly cut-off at the same time: Cleaver’s Soul on Ice, Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers, Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur.

The only people that maybe read Whoreson before Goines sent it out to publishers, would’ve been Goines’ peers in Jackson Penitentiary. And so, Whoreson is a manuscript edited entirely after the fact, pragmatically cobbled together, with only the most glaring errors and concerns fixed before publication. Dopefiend indeed, had some outside input during the writing process.

Whatever the “reasons” behind the drastic improvement in Goines’ writing, plotting, and structure in so short of a time, it’s commendable. Plenty of authors with MFAs in Creative Writing never develop such a clear, distinct, and influential voice. It really only takes Goines one book to find his voice and to stop aping his primary influence—Iceberg Slim. Unfortunately, we had to spend a month on the voiceless book anyways.

Whoreson begins as a weird, stretched-out version of a 60s party-record joke or Iceberg anecdote: A prostitute has a baby and names it Whoreson! That name though, also injects the rather uneven novel with the kind of inevitability that’s Goines’ specialty. In Dopefiend, the suspense was never “if” (if Terry will get addicted, if Terry will prostitute herself, etc) but “how”. Whoreson takes that even further, as the character’s name and upbringing—Whoreson’s prostitute mother Jessie trains him on how to be a pimp—leave no question as to what Whoreson Jones will do with his life.

Goines though, introduces a middle-class contrast to this street-life fatalism. In Dopefiend, Terry’s struggle with addiction is heartwrenching, but always a bit absurd and eventually tragic, because she could’ve returned to her parents for help. In Whoreson, it’s childhood friend Janet who returns throughout the narrative to test Whoreson’s pimping complacency. Goines isn’t a fatalist, he just doesn’t have much hope that people, given the chance to change, actually will. He underlines this point by providing other options for his characters—it’s just rare that his characters take advantage of these options.

As early as page 30, Janet asks, “What you goin’ to do, Whoreson, when you get grown?”. Whoreson later sees her performing (“this girl had STAR written all over her”) and after the performance, he helps her escape a wildly enthusiastic crowd and she basically repeats her interrogation from earlier in the book (145-146). Though Whoreson predictably views her as square and a mark, it’s clear that like Billy, Terry’s high school friend in Dopefiend, the reader’s intended to realize that the square’s correct here.

The Janet character and the Whoreson/Janet relationship are horribly underdeveloped and it’s to the detriment of the book, especially the ending. Why Janet cares about Whoreson doesn’t make sense. And that’s not from a contemporary feminist reader point of view—i.e Why would a woman be attracted to a such a jerk?–but because Goines doesn’t even sell it. In a book about pimping, it’d be easy for there to be some kind of aside about how all women want to be used or abused or a suggestion that Whoreson’s just that damned smooth, but none of that’s there. That’s because Goines’ novels aren’t the least bit glamourous, while Slim makes sure to retain some of crime’s appeal. And so, we’ve basically got a character that’s part Iceberg Slim inner-city legend and part, scrappy street kid.

Look at how often Goines humiliates Whoreson. The hilarious scene where Whoreson takes an in-labor Boots to a Dermatologist (“I couldn’t pronounce the damn word let alone spell it”) shows how ignorant and useless he is in the real world (130-131). In the scene where Whoreson meets Janet’s record label friends, Whoreson’s completely out of his element—he knows as much “wonder[ing] if [he's] that far out of [his] depth” (270).

Moving back through the book, Whoreson’s story is really nothing but these types of embarrassments, these reminders that he’s clueless—in the straight world for sure, but how many times is he played by a fellow pimp or one of his prostitutes? Indeed, the book ends with Whoreson going back to jail…because of Boots. The ending’s all injected with some hope and excitement about when he gets out and it’s hard to tell if we’re to read this as ironic—because when the book isn’t turning Whoreson into a chump, it’s making him out to be the greatest pimp in the world—or sincere. Are we to believe Janet is going to hold out for him? Is he as clueless as ever? Ultimately, it doesn’t matter and that’s the crux of why Whoreson isn’t very good: There’s no consistency to the book, it doesn’t make sense.

Go back and the beginning and look at all the meaningless transitions. Goines literally takes advantage of the autobiographical, first-person style grabbed from Slim to provide the illusion of structure to what is basically a bunch of anecdotes. Chapter Three begins with a reference to Whoreson’s “first days in school” and on the next page, there’s a quick reference to his “ninth birthday” (18-19). You’ll notice Goines continually reminds readers of Whoreson’s age—he’s only twenty-four at the end of the book—or references time (Chapter Four, ridiculously begins “Winter came and went”) but none of it means much of anything (28). This is perhaps the most glaring example of the many small inconsistencies and mixed-up details in the book.

At the same time, some of these details–often the same ones that make Whoreson so schizophrenic—create some of the book’s best and most telling scenes. In particular, there’s an absurd humor that hardly ever shows up in Goines’ later work. Once again, the influence of Iceberg Slim here probably justified this humor (there’s also a few times where Goines employs some of Slim’s jazzy language) but the humor at times, does Slim better.

Early in the book, Whoreson and Tony are arrested for their involvement in a craps game. A cop grabs Tony and orders him around (“Spread your legs nigger”) while the other cop takes care of Whoreson. The cop asks the half-white Whoreson, “Boy, what the hell color are you?” to which Whoreson answers “colored”. The cops slaps Whoreson and then orders him: “Get up against that car, you black sonofabitch you” (33). This humor’s closer to the depressed absurdity found in Chester Himes’ writing than the dirty old man jokes of Slim. The scene is hilarious and vivid—Goines doesn’t write it in, but you can imagine a beat of confusion before the cop slaps him—and a brilliant illustration of race as a social construction.

Real quick aside that won’t fit anywhere else: Whoreson’s mixed racial heritage is really fascinating. Not only because it allows Goines to employ satire like the scene above, but because it’s an early example of Goines’ obsession with white privilege. Like, the white racist cops that scare young Whoreson and Tony and steal all their money, Whoreson’s father is a white person who reaps the pleasures of illegal activity but due to institutionalized racism, none of the repercussions. The white john returns in many of Goines’ other books–and here it’s Whoreson’s father. There’s also the scene where Goines blurs the borders between legal and illegal business—Whoreson calls Johnnie Ringo, the white (and less successful) musician once engaged to Janet, “a high-paid pimp” (274).

Thing is, Whoreson’s sorta right. But he’s hardly a wise anti-hero, just a guy with a decent bullshit detector. There’s something hilarious about the way Whoreson breaks down Janet’s ex-fiance and it’s an extension of their earlier interaction in prison where Whoreson affects the voice of a righteous brother to mock/impress Janet:

Many people think we’re sick, but it’s not really a sickness. As I now see it, it is not the eccentricity of a single individual but the sickness of the times themselves, the neurosis of our generation. Not because we are worthless individuals, either, rather because we are products of the slums. Faced with poverty on one side, ignorance on the other, we exploit those nearest to us.” (187)

“If you use good diction,” Whoreson tells the reader, “you could con a bee out of honey” (187). It isn’t simply “good diction” though, it’s a vicious satire of 60s social theory. Though Goines doesn’t approach the topic with humor again, a disgust with the jive of political progressivism returns in many of his books.

Whoreson also indulges in some pitch-black, just plain cruel humor that’s very Slim-like and uncharacteristic of Goines’ other work. Violence/abuse in a Goines novel is usually swift and unexpected. It usually reads like he’s holding back out of propriety or kinda bummed-out that his narrative has to go in that direction. In Whoreson though, he just goes for it. Four scenes stand-out:

-When Whoreson stuffs Little-Bit into a trashcan (111).

-The S & M freak who gets-off on Whoreson’s beating (120).

-The exercise routine he puts the overweight prostitute Ruby through (214).

-The mock-wedding between Whoreson and Stella (256)

The first three are just weird, violent kinda hilarious asides, but the fourth, like the “Boy, what the hell color are you?” scene is pretty brilliant and unfortunately, unlike anything in Goines’ later work. There’s the recurring joke that Stella thinks Whoreson’s name is “Johnny” and the whole absurd situation of a mock wedding, attended by a bunch of drunks, in a fake-church and it’s just brilliantly portrayed. As is this hilarious explanation for why Stella, besides the fact that she’s a dolt, doesn’t suspect anything: “If Stella had been black, she would’ve been hip immediately, but she had never been in black church before, so whatever she saw was bound to look strange” (257-258). We’re in Himes territory and it’s shame Goines didn’t employ this in his later work.

Another rather effective “mistake” is the shift in Chapter 26 from first-person to third-person. In a more critically respected novel, this abrupt move away from Whoreson’s perspective, at the moment that seals his fate, would be ripe for analysis. In something as sloppy as Whoreson, it’s more like a happy accident—the byproduct of a hurried manuscript. Goines probably did it because it was easy and built-up tension—narrative modes be damned—but it’s really effective. The book really opens up here. It feels like all the other Goines books because there’s gears turning, there’s contrast and tension–and that feeling of inevitability.

This is what I mean about Whoreson being a work of Juvenilia. Whoreson bounds, impractically and awkwardly from one sensibility to another. Goines takes Iceberg Slim’s writing style, this folksy, mythic or mock-mythic storyteller style that’s equal parts dark and hilarious and compartmentalizes it. Whoreson goes through three shifts in style, the first two, derived from Slim’s work, the last, an early version of Goines’ sensibility.

1. The early parts of Whoreson are through a playful, Iceberg Slim storytelling style–a kind of idealized, consequence-less childhood, all set in the slums of Detroit. It’s telling that Ghostface name-drops Goines in “Child’s Play” from Supreme Clientele: “Lines from Dolemite, a few tips from Goines/Birthday, I gave her two fifty-cent coins”. Whoreson’s idyllic youth ends when the mother of Whoreson’s friend Tony dies of a drug overdose and Whoreson loses his mother to consumption some pages later.

2. After those deaths, Goines drops the comedic, consequence-less side of Slim’s writing and embraces the dark, shooting-from-the-hip style that made Slim so popular. What follows is Whoreson’s pimp education and also the reader’s education on pimping. We’re treated to a colorful cast of whores and pimps; the book is no longer a mess of anecdotes.

3. Once Whoreson is in jail and when he returns to the streets, the novel gets Goines-ian. Less interested in educating and “exposing” the underworld and more interested in paying-off the narrative threads set-up in the previous 180 or so pages. Pimping, whoring, hustling, etc. are all realities to the reader by this point. Nothing is shocking. We’re just watching events roll-out. It’s “matter-of-fact” like the next fifteen Goines novels.

Looking at it that way though, the novel kind of works. It’s structured in a conventional, teachable way and the shifts in style are justified. The shift after the death of Jessie and Tony’s mother seems intentional: Your typical first act turning point. Of course, Goines slips in some on-point characterization too. In the scene where Jessie’s confronted with the death of the mother of her son’s best friend, she simply acts, out of human obligation. Whoreson even comments that he assumed Jessie would find a way to “refuse to go”, but she doesn’t (50). This is part of the genius of Goines: His understanding that human beings are not static, how and why they act is unpredictable.

If there weren’t so many smaller, off details or just nutty characterizations and indulgences, Whoreson would be an artful pastiche. An exercise in sub-genres injected with Goines’ talent for making crime and life completely unappealing. What makes Whoreson a failure is not the story as a whole—though the ending is hard to take seriously—but the amount of smaller details that are just off: loose narrative threads, confused characterization, too many styles fighting with one another.

At the beginning of this essay, I said it only took Goines one book to find his voice and drop the influence of Iceberg Slim. Really, it only takes Goines two-thirds of his first book to drop the Slim influence. Though the book’s conceit–the gritty, first-person tale of a career pimp—is pure Iceberg (Goines basically takes the style of Pimp and swipes the plot from Trick Baby), Goines’ sensibility breaks through as it moves from a story of how a pimp became a pimp, to the day-to-day, hustle of being a pimp. The former is the broader, street-educating perspective of Slim, and the latter, the in-too-deep, regular-ass details of crime that come to define the Donald Goines style.

This month’s book is ‘Black Gangster’, see you at the end of the month-b

SOURCES CITED

-Allen Jr, Eddie B. Low Road: The Life & Legacy of Donald Goines. St Martin’s Press: New York, 2004.

-Goines, Donald. Whoreson. Holloway House: Los Angeles, 2004.

Holloway House’s decision to delay publication of Donald Goines’ first manuscript Whoreson until after Dopefiend frustrated the just-out-of-prison writer then, but viewing Dopefiend as Goines’ debut is ideal when looking at his oeuvre. Whoreson is best viewed like a popular writer’s early, usually unpublished works: It’s soaked in its influences (Iceberg Slim and presumably, confessional works like Soul on Ice) and is really only of interest for the half-formed ideas that would later come out whole.

Holloway House’s decision to delay publication of Donald Goines’ first manuscript Whoreson until after Dopefiend frustrated the just-out-of-prison writer then, but viewing Dopefiend as Goines’ debut is ideal when looking at his oeuvre. Whoreson is best viewed like a popular writer’s early, usually unpublished works: It’s soaked in its influences (Iceberg Slim and presumably, confessional works like Soul on Ice) and is really only of interest for the half-formed ideas that would later come out whole. Though Goines’ desire to write stems solely from reading Iceberg Slim, and Goines’ and Slim’s names are now mentioned together as the founders of Street Fiction, their work is pretty different. Goines, following Slim, approached crime and the underworld with an unflinching reality that still holds-up in 2010 and combined it with a hard-to-explain, unconditional empathy for the characters. Unlike Chester Himes, who did similar things, the law and order element is all but gone in Slim and Goines’ work and that’s crucial.

Though Goines’ desire to write stems solely from reading Iceberg Slim, and Goines’ and Slim’s names are now mentioned together as the founders of Street Fiction, their work is pretty different. Goines, following Slim, approached crime and the underworld with an unflinching reality that still holds-up in 2010 and combined it with a hard-to-explain, unconditional empathy for the characters. Unlike Chester Himes, who did similar things, the law and order element is all but gone in Slim and Goines’ work and that’s crucial. Real updates coming soon…

Real updates coming soon… So, I thought about putting up a kind of obnoxious message about how the “New Year’s resolution” for everybody reading and writing about rap on the internets should be some attempt to at least like, foster discussion?

So, I thought about putting up a kind of obnoxious message about how the “New Year’s resolution” for everybody reading and writing about rap on the internets should be some attempt to at least like, foster discussion?