This week’s Village Voice has a piece I did on Little Brother and their excellent new (and last) album, Leftback. I hope I did the group justice and unfortunately, I totally didn’t get to explain all the mini-reasons why Leftback rules, but well, go listen to it if you haven’t already. There was also a special kind of thrill getting to hear the album early in Phonte’s car and also, sitting down with Phonte and Pooh and just talking about rap. Also, thanks to Eric Tullis for helping me get in touch with Little Brother.

One thing, that’s much too “bloggy” to discuss in an article though, is how I find the music of Little Brother (and also, Slum Village) to be much more edifying than their supposedly better, certainly more influential rap 90’s rap influences. And this isn’t a case of what I heard or was intimate with first–Pete Rock and Tribe, is the earliest rap shit that got me into this rap shit–but there’s just something kinder, wizened, and more free in Little Brother or Slum, you hear age and wear and confusion in their raps and at 25, that grabs me more. Anyways–here’s the article:

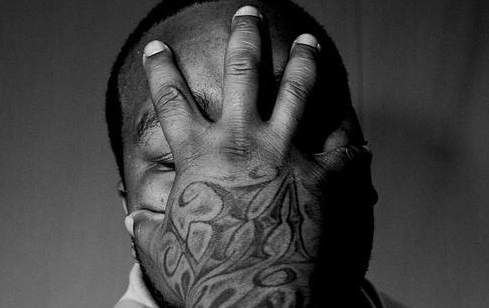

It’s near midnight on an early April weekday, and as Little Brother emcee Phonte Coleman navigates North Carolina’s I-540 between Raleigh and Durham, the group’s latest (and unfortunately last) album, Leftback, jumps from the speakers. He nods his head to the syrupy beats, mouths the words to his and partner Big Pooh’s raps, and occasionally swings his fingers across the dashboard, playing along to a particularly immaculate keyboard line. “Originally, it wasn’t supposed to be this kind of an event,” he notes, casually, when it’s over, reflecting on the weirdly formal, strangely mature end to the underground hip-hop institution his group became.

A big, dumb thesis on Little Brother’s break-up marking the end of “conscious rap” could be drummed up pretty easily, but that lofty label never meant much to the group. With 2003’s The Listening, then-trio Phonte, Pooh, and producer 9th Wonder were handed the responsibility of resurrecting rap simply because that satisfied debut housed sensitive, working-class rhymes and vaguely throwback production. Ignored was the fact that they were just as likely to clown “next-level” vegan nonsense-spouters as they were radio-rap knuckleheads.