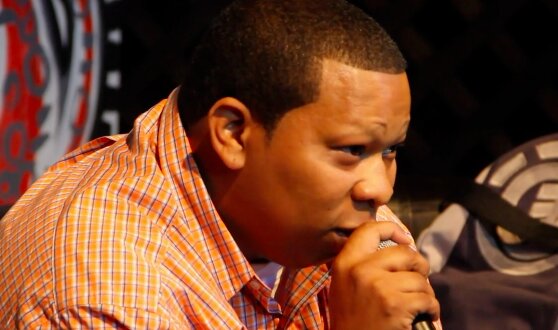

There are like, infinite gems in this Red Bull Academy interview with Mannie Fresh, but the one I’d like to focus on comes about an hour and thirteen minutes in, when Fresh answers a question about producers he’s currently feeling. His list is Drumma Boy, Shawty Redd, T-Mix, and Beanz & Kornbread, who are all basically Mannie Fresh disciples (okay, T-Mix is more like a peer), but Fresh’s discussion of how the record labels have good reason to hold these guys back, so that there isn’t well, another superstar studio nerd like Mannie Fresh is pretty fascinating:

“The people who I name right now, if they were sitting on the sofa with me, you wouldn’t know them, because it’s almost like, that’s the way record companies want it to be. They don’t want you to get too far, where you can start naming your price and doing certain things or whatever.”

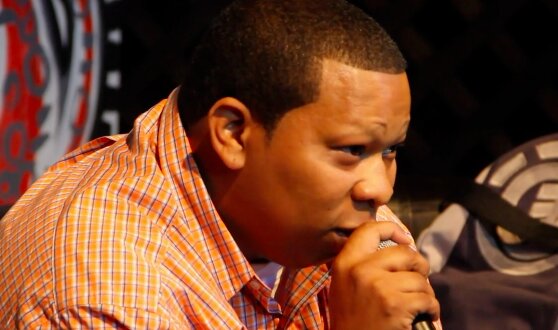

Fresh’s cynicism is kinda ideal. He rose to fame with Cash-Money and basically built the label, but he got pretty fucked over by them or at least, Birdman Zuckerberg-ed him at some point or another, but he isn’t bitter about it. At least not publicly. He’s of course, also given hits to plenty of rappers outside of Cash-Money, so he’s dealt with major labels too. Though his output’s slowed down as of late (Hurricane Katrina and your sister being murdered will do that to you.), he’s shifted to DJing live sets and doing stuff with his own independent label, Chubby Boy Records (last year’s Return Of The Ballin was minor but excellent nonetheless). The point is, Fresh comes from a pretty rarefied perspective when he gives us all one more reason why the majors are kinda evil.

On the major label level, hip-hop producers are increasingly viewed as disposable. In my Spin column two weeks ago, I mentioned the majors’ slash-and-burn approach: A regional production style arrives on the radio and then is sucked dry until we’re all sick of it (Lex Luger, you need to watch out) and then, it’s onto the next one. Running parallel is a generic, even easier to repeat “pop-rap,” style that absorbs the signifiers of a regional sound and allows a bunch of middling, kinda-alright producers to do a lot of the work on most of the pop-rap hits. Either way, the work’s spread out amongst as many cheap, desperate producers as possible, or handed over to the few major label golden boys. If that producer isn’t a star like Kanye West or Will.i.Am, the plan’s to keep him invisible.

This approach extends beyond hip-hop too. Britney Spears’ “Hold It Against Me” features a dubstep breakdown but the song is produced by Dr. Luke. Just a few years ago even, this kind injection of sub-genre would’ve been accomplished by bringing in an actual person who makes that music (indeed, at some point, Rusko was working with Britney Spears) but now, thanks to technology and a feckless industry, we simply get a facsimile of the style. It’s just as likely that Rusko was just paid a bunch of dough to hand over his dubstep beat, but either way, it represents a hardheaded, closed-circuit approach to musicmaking that’s going to be pretty lethal to both the producers being fucked over and the producers/labels doing the fucking over.

The wholesale jacking of a sound or style isn’t anything new to the music industry and ghost-producing is quite simply, part of the game, but there’s something more nefarious going on here. Previously, regional sounds were able to sneak in, if not immediately, but over time. Now, all in an attempt to keep the industry afloat by protecting the ten or so money-generating artists and producers, regions and the underground get rolled up in the major label sound in careless, selfish ways.

There is some hope however. It’s worth nothing that the recent awesome and mostly Chris Brown-less Chris Brown single “Look At Me Now,” is produced by Diplo and Afrojack, which is nice to see after Will.i.Am took a break from ripping off Baltimore club to pretty much swipe the loping, drooping bounce of Afrojack for The Black Eyed Peas’ “Time Of My Life (Dirty Bit)”. Even more interesting is how the next wave of auteur producers aren’t all that interested in making hits or talking to the majors. Producers like DJ Burn One, Araabmuzik, Clams Casino, and The Block Beattaz, who don’t exactly need the majors and don’t even make beats that court that sound–because well, what’s the point anymore? Major labels are so protective of their very few moneymakers, that they’ll do anything to keep it “in-house,” even if it means slowly but surely killing the industry’s future creative opportunities.