Salem make a gothic, syrupy kind of electronic music and the touchstones of their sound are the slowed-down, choppy drums and vocals of Houston screw music. On some songs, such as “Trapdoor” (the title itself, a play on the horror movie elements of their music and their love of coke-slanging “trap-rap”), the rapped vocals of the all-white, Midwestern group creep along, slurred, heavy with bass–like a DJ Screw freestyle. These quasi-raps are punctuated by the word “bitch,” threats of rape, and some clear pronunciation nods to Southern rap. Streets is “skreets” for example. A lot of people, like Christopher Weingarten think this is pretty offensive. A lot of other people, like Larry Fitzmaurice are just like, “nope.” Others, including the group itself—defend the vocals as simple, vocal manipulation.

Well, it’s not. The slowed down vocals do not only have the effect of bringing the vocalist’s voice down to stoned crawl, they make the white performer sound black. This, coupled with lyrics that are content-wise, what my grandmother thinks rap’s about (murder, rape, misogyny, repeat) and the problematic, conscious “hip-hop” pronunciations underneath that vocal effect, makes Salem’s music pretty egregious. This is a group of white kids who’ve screwed their vocals down to “sound black,” and then use that screwing-down of vocals to say things they wouldn’t–and couldn’t–say otherwise. Employing the word “minstrelsy” is controversy-baiting, but it also isn’t that far off.

Songs like “Trapdoor” also do a disservice to screw music and southern rap by reducing it to aggro-violence and tough-guy sexuality. There’s a communal joy in those DJ Screw freestyles. There’s a sense of humor and word-obsessive fun on Gucci Mane songs. And the production isn’t relentlessly dark. You don’t screw Junior’s “Mama Used To Say” if you’re trying to be all tough and scary.

When the “this shit’s offensive” discussion really started to pick up, it turned into a debate about “authenticity” when that was ultimately besides the point. Ignoring the musical issue (that King Night is much less sonically sophisticated than the stuff it’s ripping off), which has nothing to do with “authenticity,” there isn’t really any degree of “authenticity” that could justify these dopey kids changing their voices to sound like Project Pat and then, saying “bitch” a whole lot.

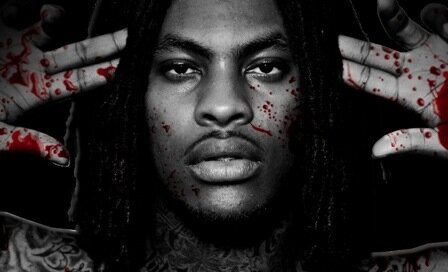

Plus, Salem are plenty authentic. If the game here is “authenticity=struggle” etc. well a group of midwest fuck-ups who had or have drug problems should be awarded some major points. My guess is that they feel like they relate to the “fuck the world” feeling of DJ Screw freestyles and Waka Flocka’s fight rap just like they relate to black metal’s nihilism. And that’s interesting! And awesome. Good to see artists reaching into music beyond what they’re “supposed” to reach into and also, it’s the internet era, age of information, etc. so really, why wouldn’t these Salem kids who clearly like Gucci Mane or Chicago Footwork cram it into their music? Fusion! Yes! For extra “authenticity” points, Salem hail from Chicago and Detroit and so, they have something resembling a direct connection and understanding of this stuff.

Only they don’t. The group really show their asses in this XLR8R interview. Salem’s Jack Donoghue calls footwork wunderkind DJ Nate’s music “smart,” but adds, “but I don’t think he’s trying to be clever.” DJ Nate is most certainly trying to be clever. That’s what sample-based dance music like footwork is all about: consciously flipping the weirdest, funniest, most dope sample in the coolest, smartest way possible. Heather Marlatt, photographed for the magazine in cornrows, describes her interest in “Juggalos” but not the Insane Clown Posse’s music, which seems the inverse of Salem’s interest in black music: who cares about the people, it’s all about the sounds, man.

Later in the same interview, John Holland dismisses the whole “hey, it’s fucking weird that these kids are making themselves sound like black guys” argument with this: “It’s not like we’re Elvis Presley…what are we robbing the music from a different race? Give me a break!.” That’s of course, exactly what these guys are doing. But that isn’t what’s troubling people about the group. It’s that inexcusable and naïve employment of the screw vocals for something far beyond a sonic effect.

Notice, that despite Salem’s “authentic” pedigree (ex-junkies and troubled youths, from the birthplace of at least some of their sounds, etc.) the group’s defenders rarely take the “authenticity” approach to justify the group’s music. Instead, they play the “post-authenticity” game, which steps around “there’s some racially problematic stuff about these kids” altogether. It says: none of that stuff matters anymore. The floodgates are open bro, get with the program! “Post-authenticity” starts to sounds a lot like “post-racial” explain-aways.

When the argument doesn’t go with the “authenticity is dead” narrative, it reaches for “authenticity never existed.” There will be references to “fakers” like Elvis Presley or Bob Dylan, either to deflect (as Holland did with XLR8R) or as some weird, precedent: music was never authentic and the rock n’roll from decades ago (and a very different America) straight-jacked a lot of music, so it’s acceptable for people in 2010 to do whatever they hell they want as well.

Brandon Ivers, who wrote the XLR8R piece, articulates that “post-authenticity” angle well: “Salem embodies a generation that doesn’t care about race, sexual orientation, authenticity, and a lot of other stuff that used to be a big deal.” There’s some irony in Ivers’ statement but he’s completely on the nose when it comes to Salem: they don’t care. And the music fans and critics embracing these clowns don’t care either.